This a monthly series which I have been publishing for years. You can subscribe here, to get the latest cheese delivered directly on to your screen.

Yes, I’m a week late for this cheese of the month. But there was so much cheese going on over the weekend that I hope and trust the great gods of cheese above (as well as you, my readers and followers down here) to show leniency… in return I’m bringing you this true mountain cheese from the Allgäu, which the great guys from Jamei had on offer at the cheese market of the StadtLandFood festival (no, I won’t even start to rave about this incredible event we managed to make happen… we’d never get to the cheese if I did).

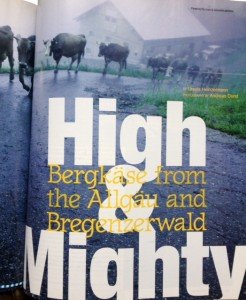

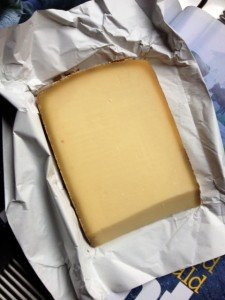

17 months can mean anything for a large wheel of alpine hard cheese, from too old, dry and boring to full of life, just starting to show its full potential of complex yellow fruit aromas and spices. Needless to say that the latter is the case. Some years ago, I’ve written about the alpine dairy this cheese comes from in Culture, the American cheese magazine:

17 months can mean anything for a large wheel of alpine hard cheese, from too old, dry and boring to full of life, just starting to show its full potential of complex yellow fruit aromas and spices. Needless to say that the latter is the case. Some years ago, I’ve written about the alpine dairy this cheese comes from in Culture, the American cheese magazine:

Meepmeeeep, meepmeeeep… my alarm. It’s pitch-dark, and I can hear rain. Where am I? Only 4 am… then I suddenly remember: I’m at Alpe Oberberg, with cheesemaker Gudrun and Klaus Beck, on the Mittagsberg mountain between Immenstadt and Sonthofen. The Becks are by no means the only ones producing cheese in the Allgäu … but the large wheels Klaus Beck produces are among the very best. When I arrived yesterday in the afternoon, he took me down to the quiet, humid cellar for a taste… thinking of the elegant, discreet and yet intense aroma I jump straight out of bed …

The wiry, energetic Beck is already busy in the cellar, clad in a long white apron, turning and washing his cheeses, after having taken yesterday’s wheels down and put them into the salt brine tub.

Gudrun and Klaus Beck start early in order to get done with cheese-making before the first hikers arrive. They are the fourth generation of their family to run the Oberberg dairy. Each year from May until early November they not only sell drinks, cold snacks and Kässpatzen (a traditional cheese-noodle dish) and offer simple overnight accomodation to add to their income, but also do tours to raise awareness about the mountains, their life and their cheese. „I pretty much grew up here at the dairy“, 53-year-old Klaus Beck told me yesterday, „during summer, they didn’t see me very often at school.“ Eight farmers entrust them with their cows, 33 animals in total, whose milk they buy from the owners, deducting a certain amount for „board and lodging“. Alpe Oberberg offers its summer lodgers almost two and half acres mountain meadows per head which are grazed upon a sophisticated rotation system. The pastures are at 4430 feet and above – the higher, the more omega-3 fatty acids the milk contains and the tastier and more complex the cheese, says Klaus Beck.

In the shiny white-tiled dairy the soft-spoken Gudrun Beck skims the yellow layer of cream from yesterday’s evening milk that has been left standing overnight in a shallow stainless steel vat. Maturing and skimming some of the milk is important to make good cheese, she explains, putting more wood on the fire under the 215-gallon round copper kettle – round cheesemaking vats which are called Kessel. Until they built this new dairy ten years ago, they made cheese in the hall of the old wooden house, in a round copper cauldron suspended over an open fire. Now the fire is enclosed and subterranean and can be moved under a water boiler, so that for cleaning they don’t need to heat water on the kitchen stove anymore – „but it’s still a lot of work“, Gudrun Beck remarks. „However after a hundred days, when the cows go back down, and we have a quieter month before we follow them and move to our winter home in the valley, then something is missing.“ It’s slowly getting light, and I can hear the cow bells approaching like an early warning system with its very own harmony – the morning milk is coming! Milking in the neatly swept wooden stable under the house seems like a timeless game of movements and gestures of all involved, accompagnied by the ever changing rhythm of the bells. As soon as the last of the greyish brown cows – most of them Brown Swiss – has been freed of the vacuum milkers, Klaus Beck changes back into his dairy clothes and watches the milk heating, slowly stirred by a paddle. He insists on carrying the milk over in cans instead of having a pipeline installed – any avoidable movement means less flavour in the cheese, he says. He adds natural rennet and his own whey-based bacteria culture, stopping the paddle. Time for a quick breakfast which I now feel rather desperate for, whereas they seem utterly absorbed in their work.

After about half an hour Klaus Beck thoroughly cuts and stirs the now coagulated milk, all the time raking the fire, as the curd needs to be scalded at 125°F. After preparing two large adjustable hoops on the draining table and lining them with cheesecloth, he takes a handful of curd from the steaming whey, presses it testingly and looks at its consistency. He seems satisfied and suddenly switches from slow motion to quick step. With a large cheesecloth, one of its borders folded over a long flexible metal rod, he dives into the whey along the kettle’s wall while his wife holds the two other corners of the cloth. Up comes about half of the curd, a big knot and a powerful swing move it over to the table and into the first hoop. The whole procedure is repeated, then he adjusts the hoops, folding the cloths carefully over the two white embryonic cheeses, puts a wooden board on each of them, finally the press piston on top and tightens it. Only moments later the kettle’s copper is back to a shiny glow and Klaus Beck turns the still wobbly wheels for the first time, carefully smoothening the cloths to get an even rind. That’s it!

Nine o’clock, time to check the fences so that the cows can go back to their pastures. In a long green loden coat, big floppy hat and wellies he’s ready to trudge out onto the wet mountain. He seems completely at one with the world up here, and the extraordinary character of his cheese, its perfect balance between intensity and lightness seems to grow out of his own inner harmony. Like most Alpine cheesemakers, the Becks are strong advocates of raw milk and often bewildered by the problems this leads to with some authorities. From their point of view it is obvious that the latest in technology doesn’t necessarily mean progress. „You know“, Klaus Beck tells me before he disappears into the misty green, „for a long time I worked as a lumberjack during the winter, but I’ve given this up and now I can go skiing all the time. On skis in the mountains, that’s the most beautiful thing on earth…“ His eyes light up at the thought of it.

Klaus Beck died in April this year while skiing in the mountains. His family goes on running Alpe Oberberg, the family dairy, and he lives on in his cheese.

This a monthly series which I have been publishing for years. You can subscribe here, to get the latest cheese delivered directly on to your screen.

If you enjoyed reading this, you might consider clicking on the button below and supporting me in my work. I’d be more than happy. Thank you.