It’s been ten years since Torontonian Arlene Stein started the Terroir Symposium in her native city. About one year ago, Arlene moved to Berlin, and we met, and she invited me to speak at this year’s event (of which she also created a more intimate satellite version in Berlin in mid-May, but that’s a different story). Me being travel-insatiable me took this as a wonderful excuse to be on the road for a whole month, going to New York, Cambridge, upper Vermont, Québec, Nova Scotia, and, extensively, Ontario. For wine, for cheese, for friends, for…life as such!

And then, as a grande finale, the long, wonderful weekend of Terroir Symposium. I was staying with my colleague and friend, food writer Naomi Duguid, which meant that I got immersed into the local food scene without much ado. Sooo much happening in this truly multicultural city!

To give you just one example: Wychwood Farmer Market is a must on Saturday morning (and a great run back to south of the university where Naomi lives). It seems that every time I come to Toronto (mind you, that’s only been every second year so far), the market celebrates its first outdoor day, and everybody is extremely joyous and happy (but they probably are the same anytime). All sorts of greens, fresh fish, great bread, honey… gorgeous.

And cheese: the very best fresh cheese, that is quark, I have eaten for a long long time (and this comes from somebody who has quark on rye toast every morning). It came from the radiant Ayse Akoner (and her German-Canadian husband Jens Eller) of Marvelous Edibles Farm 2.5 hours northwest of Toronto. She is milking just one Jersey cow (they also have pigs, ducks, eggs, lots of fresh and pickled vegetables) and turning the milk mostly into yogurt and fresh cheese. What a fine texture and fresh, clean taste… She pasteurizes the milk, adds starter cultures and rennet, and lets the curd drain, first on trays lined with muslin cloth, then taking the cloth up and hanging it. Altogether, it doesn’t take longer than six, maximum eight hours, she told me. Together with the very fine sourdough bread from Dawn and Ed of Evelyn’s Crackers (yes, they make excellent crackers), Ayse’s quark made for a perfect breakfast and a very happy Heinzelcheese.

Then, the symposium – I co-moderated a Riesling panel, together with Magda Kaiser of Wines of Ontario, Christoph Thörle, Robert Gilvesy (on the right in the plane on the way to our outing in Niagara) and Charles Baker, featuring a great selection of their wines as well as some from British Columbia and a whole row from Ontario. The sold-out tasting for almost a hundred keen symposiasts took place in the Italian Gallery of the Art Gallery of Ontario, possibly the most spectacular venue I’ve ever hold a tasting in (and also one of the best organized – that group of sommelier volunteers was simply perfect, and I wish I could beam them over to Berlin for some events! Thanks guys!!!).

Arlene also asked me to give a talk on wine in Canada, of which I am a big fan. And instead of going on and on and on about it, here is my talk, for those who are interested. For all others: it’s been a great event, I met a ton of fascinating, inspiring people, and I hope to be back next year.

Talk at Terroir 2017: A non-Canadian’s view on wine in Canada

I love Canada. If it didn’t exist, one would need to invent it, for all kinds of reasons. You Canadians have shown during the past decades how much a country can change. It’s not that Berlin, my home town, did not change since I first came to Toronto in 1985 as a young chef, but hey, back then, you guys (not you exactly, of course) served us green peas and mashed potatoes with absolutely everything. And wine, well, our tour included a tasting at Inniskillin and I didn’t have a clue of the stuff back then. But I remember that we had icewine, and I remember that Canadian wine was like Berlin at that time, before the wall came down: somehow different, and in a way embarrassing. Whereas now – look at us. When I mention coming from Berlin, people beam at me. And the wines of your country are such a joy.

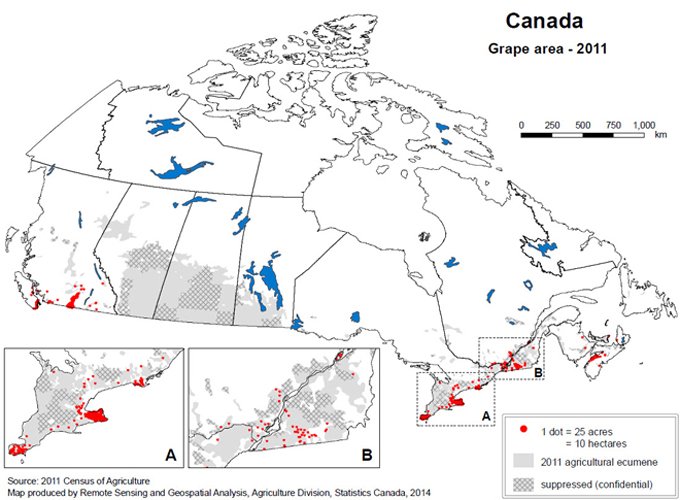

When I say I love Canada, I have in fact seen very little of its almost ten million square kilometers. But I’ve seen quite a bit of the 121 square kilometers (12,100 hectars) planted with vines (according to the Canadian Vintners Association), last year in the Okanagan and Similkameen, and right now prior to the symposium in Québec, Nova Scotia and Ontario. You’ve come a long, beautiful way.

And it’s wonderful to be here and immerse myself in those wines. Because let’s be realistic: back home it is damn difficult to get hold of all that goodness. Which means that except for some super-connected freaks most European wine lovers still associate Canada with icewine. Nothing against it, but, well… Perhaps one could take down a few more walls, and make it a little easier for everybody, work on the restrictions on wine sales and shipments. But I’m optimistic – who would have thought the Berlin wall would ever come down?! One day, my colleagues back home won’t automatically think ice wine when I say Canada, just as over here the mention of German wine nowadays hopefully evoques more then Blue Nun and Black Tower.

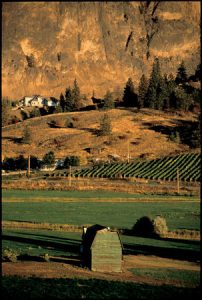

So, let me share a few thoughts on Canada and wine. When I visited the Okanagan and the Similkameen last summer, I was struck not only by the beauty of those regions, but also by the great diversity of a relatively small area. As you all know, the Okanagan from north to south basically includes everything from acidity driven “northern” Riesling to hot climate, rich “southern” Cab, Merlot and Syrah. And that’s not even mentioning the very special situation in the Similkameen with its gorgeous mountain scenery. The same is true here on the east coast, with Nova Scotia, Québec, and the richness of Ontario, from the sandy beaches of Prince Edward County down to Niagara with the beautiful escarpment and the benches. I don’t have to tell you about the dramatic differences in clima, the diversity of soils, and all the different traditions people have been bringing to the vines and vats of Canada, the resulting multitude of grape varieties.

This diversity is something I am in a way familiar with from Germany, although it is obviously more pronounced here. Because you are a nation truly built on immigration, and you are truly on the climatic edge. Which means that on the one hand you need to adapt very precisely to the respective specific conditions, but on the other you also have a wealth of knowledge and experience flowing in from other wine cultures.

Which brings me to my point, something I’ve been hearing again and again while tasting with producers all over Canada: the hankering for a signature grape variety. For the one wine that would lead the market, be easy to market, the one to stand for Canada. Which variety? Well, nobody said it quite directly (after all you are polite Canadians), but well, hmm, Pinot Noir…

Now, don’t get me wrong, I love a good Pinot as much as anybody else, and I have come across some pretty impressive ones over here. But reduce all that beautiful diversity to one variety? Make this fickle holy grail of all ambitious vintners your one and only variety? Even as a holy trilogy with Riesling and Chardonnay that would be a bad idea. You would loose so much more than you’d gain.

Of course you all realize how important diversity is. We need diversity on so many levels, in fact all levels, from the microorganisms in the soil to us people – the more diverse, the more resilient – and interesting! The challenge is of course that there are all those temptations to streamline, simplify, make things more efficient… My father is an engineer, believe me, I know what I am talking about. So it’s good to remind oneself again and again why we need many different ways to live.

To get a different angle on this, I would like to quote the great Jane Jacobs. I am sure many of you are familiar with her. A brilliant mind and very successful writer on urbanism, she moved from New York to Toronto in 1968 as an act of opposition to the Vietnam War. Urban planning and the life of and in cities really was her passion – I wish I‘d met her, and I hope she liked wine! You may wonder what urbanism has to do with wine. Well, I like to think of the wine industry as a kind of urban organism we build on the land. The way we organize our cities, the way we live in them, has lots of parallels with how we organize our wine industry. Therefore, over to Jane Jacobs.

In a speech she gave in Hamburg in 1981, on how cities develop and are renewed, she said: “All new ideas start small and all new ideas, at the time they emerge, flout the accepted ways of doing things. By the time an idea of any sort is risked in big planning, it is already middle-aged or old as an idea. Big plans live intellectually off of little plans. Big plans, precisely because they are big, are not fertile ground for fresh, different possibilities […] once in place, they are so inflexible. The greater the scale of planning, the more inflexible the result. When change impinges itself on big plans, adaptation to change comes hard. And again the deficiency is built in. It is a price of comprehension and coherence.” She goes on with an example: “The United States, for example, has become woefully inflexible with respect to transportation, not accidentally but by plan. The country’s great highway program was a twenty-year plan adopted in 1956. It was a big plan both in geographical and in time scale, and into it was dovetailed almost all the country’s suburban planning and the cities’ master plans too. Now, too late, with alternatives long stifled, the side effects of this grand planning can be seen: exorbitant energy use, pollution, land waste, and costs imposed for personal transportation on people who can no longer afford the costs.”

Let’s think a moment about what she’s saying and wine: Think about climate change, new market structures, new ideas about how industrial or natural a wine should be…

She went on: “Big plans make mistakes. […] But the objection I am raising when I speak of flexibility and adaptability goes beyond saying big plans can turn out to be bad plans. In their very nature, big and comprehensive plans are almost doomed to be mistaken. This is because everything we do changes the world a bit. Everything has its side effects and repercussions. Everything others do changes the world a bit too. We can’t anticipate all the effects and repercussions of change. Big plans render us unadaptable because we can’t adjust to the changes not foreseen in their making; we can hardly even acknowledge the changes as they become evident. We become too committed, in a big way, to our big plans. Life is an ad hoc affair. It has to be improvised all the time because of the hard fact that everything we do changes what is. This is distressing to people who would like to see things beautifully planned out and settled once and for all. That cannot be.”

Well, I can only add to that, that as a Berliner growing up in the 1960s and 70s, I have more than enough experience of big plans, fortunately from afar, as I grew up in the western part of the city: long queues, empty shelves and frustrated human beings were the result of the east German government’s big central planning.

But, you’ll say, we need to plan, we plan when we’re planting, we plan when working in the cellar, putting a wine list together. Over again to Jane Jacobs: “Does all this mean trying to plan is useless? No, of course not. Trying to use foresight, which is what planning is, is obviously so necessary and useful that most of us are practicing it constantly. […] what I am proposing is that we practice making little plans for that purpose, not big ones. I think we need to relearn the art of doing that, and that there are ways to relearn it.”

In terms of wine: listening to what is happening in the vineyard, in a vat, what customers really want, that’s the source of little plans which grow from the ground up instead of being imposed from above.

Jane Jacobs then went on to tell the story of how a group of Torontonians by the way of spontaneaous action managed to save some old houses on Sherbourne Lanes and thus initiated a different kind of building, renewal that incorporated the existing old. And she noted that big plans want to control the future, which is impossible. You have to wait for the right ideas to come along, you don’t need to decide everything, you have to leave something for the next generation, they have ideas too. Make no plan bigger than it must be: “Whenever we have the choice between making a big plan or providing instead for collections of little plans, let us choose the collections of little plans and the advantages they bring us with their diversity, fresh ideas, and flexibility.” (Jane Jacobs, Vital Little Plans, 2016, pp224-239)

Little plans mean diversity and the accumulated energy and creativity of everybody involved. An excellent example for this is Rheinhessen, Germany’s largest wine region, immediately south of the more famous Rheingau. Rheinhessen is the home of the original Liebfraumilch which as you know over the centuries was gradually exploited and cannibalized by big wine merchants’ big plans. With it suffered the region’s reputation and economy. Today however Rheinhessen is Germany’s most dynamic wine region. Why? Because a new generation, well-educated young women and men, when faced around the year 2000 with inheriting their parents’ vineyards, decided, each for themselves, to make the best wine possible instead of cheap, industrialized Blue Nun stuff for the bulk market. They did so each individually, in their specific situation, but also as friends and colleagues, not competitors. And as a result the region which for so long dragged its feet in spite of a lot of great corporate programs – big planning – finally took off again. Today it is a real dream factory of German wine, and I am very happy to have Christoph Thörle here amongst us, who with his family belongs to the first league of that development.

That is one level of diversity and the power and importance of little plans. Another of course are grape varieties. I am so happy that the Thörles, and many of their colleagues, have not abandoned the Silvaner grape, though the new VDP classification system, modelled on Burgundy (whatelse), has only Riesling and Pinot Noir deemed worthy for Grand Cru wines. I beg to differ – I think there are some great vineyards that yield much better wines with Silvaner than with Riesling.

It’s the same dilemma some people here seem to think the Canadian wine industry is faced with: to simplify makes sense for the market, but nature can and should be only streamlined up to a certain point. Grape varieties, and you know that, are not an objective by themselves, even though the market at a certain level treats them as such. On a higher level I think of them as translators, facilitators, the link between a certain place out there and its taste here in the glass. A vintner’s true art, with accumulated experience, is to find the most suited variety to translate a place into wine.

And with so many different places – look at them ((during the talk I was running a slide show of as many different Canadian vineyards I could get hold of)) – out there and in spite of the great adaptability of many of those grape varieties, we need a few more than “just” Riesling, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Again, don’t get me wrong, I do not suggest to turn back to labrusca, but I do for instance think hybrids have their place besides Vinifera.

And with that I’d like to thank you, who make and work with wine in Canada, for enriching the world with all your beautiful little plans – be it Rhys Pender‘s Little Farm Winery in the Similkameen, Alan Dickinson’s Syncromesh in Okanagan Falls, Charles Baker’s visionary ventures here in Niagara or Lightfoot & Wolfville in Nova Scotia. By all means chase the holy grail and male great Pinot Noir (because I know you can) – but leave space and energy for all the other wines that are possible in your beautiful country.

It’s been an honor and a true pleasure to share these thoughts and impressions with you, and I’d like to thank Arlene Stein and her team for this opportunity. Hopefully I managed to throw a tiny little stone into the pond of your own thoughts, which will make for a tiny wave in due time. Thank you.

(c) Ursula Heinzelmann

If you enjoyed reading this, you might consider clicking on the button below and supporting me in my work. I’d be more than happy. Thank you.